The Significance of Ethics for Mental Health Professionals

Exploring the critical role that ethics play in the field of mental health and the impact it has on both professionals and their clients. For the...

5 min read

KD HOLMES, LPC, EMDR CERTIFIED, BTTI TRAINED

:

Dec 8, 2023 8:29:00 AM

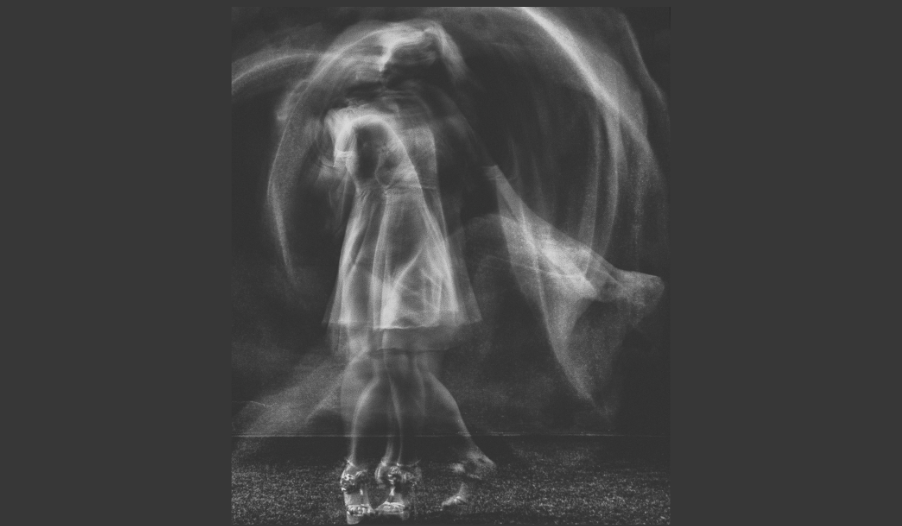

Therapy, at its essence, is like a dance-an ebb and flow of connection, rhythm, and responsiveness. This delicate dance thrives on attunement, the deeply intuitive process of building a therapeutic alliance with a client. But what happens when the dance introduces steps we hesitate to take? What happens when we introduce concepts like accountability or confront treatment-interfering behaviors (TIBs)? At first glance, these might seem like opposing forces to the empathetic, unconditional positive regard we hold dear. Yet, as therapists, can we master the art of integrating compassion with accountability? Can empathy and boundary-setting coexist harmoniously within this therapeutic rhythm?

Attunement is the beating heart of therapy. It is where safety, trust, and connection grow. Carl Rogers, a pioneer of humanistic psychology, emphasized the critical role of the therapeutic relationship in healing. His principles of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and warmth laid the foundation for the attunement process, guiding clients toward self-exploration and growth.

However, no matter how strong our attunement is, we eventually meet moments when clients’ internal or external barriers impede progress. These barriers often manifest as treatment-interfering behaviors (TIBs): coming late to sessions, missing appointments, or avoiding therapeutic work between meetings. These behaviors, while not inherently malicious, often serve as misguided coping strategies or unconscious resistance to change.

Early in my practice, I wrestled with the discomfort of navigating these moments. Instinctively, I felt compelled to address them—speaking directly about what I noticed in the room. But these actions felt misaligned with what I interpreted as "Rogerian therapy.” I questioned whether my firm stance was causing harm. At the same time, I feared that ignoring TIBs would encourage long term harm, ultimately doing more harm than good.

I came to realize that the therapeutic relationship reflects the broader dynamics of a client’s interpersonal world. How they engage in therapy often mirrors how they relate to others beyond the therapy room. If I avoided exploring these dynamics with warmth and tact, I would unintentionally perpetuate an unhelpful cycle. Therapy became the mirror in which we observed their lives, including behaviors they struggled to confront.

By leaning into the discomfort of addressing TIBs, I discovered a truth that has shaped my practice. The dance of therapy thrives when attunement and accountability coexist, forming a balanced and compassionate interaction.

Undertreatment involves "under" treating an issue by providing insufficient therapeutic interventions to effectively meet a client’s needs. This can manifest in several ways:

Minimal Engagement with Core Issues: This occurs when therapists avoid or hesitate to delve into the deeper, more challenging aspects of a client’s concerns. These might include issues such as trauma, unresolved grief, or underlying emotional struggles that are critical to address for meaningful progress. We avoid if a client is uneasy with a topic or if they think it is unrelated to their goals. Sometimes it does not matter, and other times it contributes to clients feeling stuck. Without tackling these core problems related to their presenting problem, therapy can become ineffective.

Failure to Challenge or Support Growth: Effective therapy should encourage clients to step out of their comfort zones and face their fears. Under treatment may occur when clients are not provided with sufficient tools, guidance, or strategies for growth. Without the proper support and challenges, clients may remain stagnant and miss opportunities for growth and self-development. This can occur by not confronting TIB and avoiding difficult conversations.

Mismatch in Treatment Approach: Another form of undertreatment happens when the therapeutic methods or pacing do not align with the client’s readiness or their therapeutic goals. For instance, a client may need a more intensive therapeutic approach or a different method altogether to better suit their individual needs and circumstances. Ensuring that the treatment plan is tailored to the client’s unique situation is vital to the success of the therapeutic process.

Undertreatment is a silent pitfall in therapy, where we, as well-meaning clinicians, avoid necessary conversations or fail to address presenting issues adequately. Research on major depressive disorder (MDD) reveals a global epidemic of undertreatment, with only a fraction of individuals receiving sufficient care. It’s not difficult to see how our reluctance to confront treatment-interfering behaviors can unintentionally exacerbate this issue.

Therapists, driven by empathy and fear of losing rapport, often hesitate to challenge behaviors that block progress. We focus on providing understanding and compassion but may shy away from addressing difficult patterns. Yet, unaddressed TIBs can derail therapy, reinforcing the presenting issues clients come to resolve.

Here, it is vital to remind ourselves of the delicate interplay between choice and mental health severity. Private practice therapy often assumes that client's function at a baseline level, yet the severity of some clients’ issues may necessitate a higher level of care. Part of this challenging dance involves assessing when our care is sufficient and when we need to refer out to avoid contributing to undertreatment.

To approach this complex topic, we must first define what we mean by treatment-interfering behaviors (TIBs). They may include:

Arriving late to sessions: This not only reduces the time available for therapy but can also disrupt the focus and flow of the session.

Missing appointments: Frequent absenteeism can hinder progress, making it difficult to maintain continuity and momentum in treatment.

Neglecting therapeutic work between meetings: Failing to engage with assignments or reflections outside of sessions can slow down progress and limit the effectiveness of therapy.

Changing goals in therapy each session: Constantly shifting focus can prevent the development of a consistent treatment plan, making it challenging to achieve long-term objectives

TIBs often reflect internal struggles-shame, anxiety, or even the fear of success. A client avoiding homework assignments, for instance, might fear the vulnerability or change that completing those tasks could bring.

Addressing TIBs requires us to ask nuanced questions. Is the client choosing these behaviors out of habit or resistance? Or do they stem from the weight of mental health symptoms that require additional intervention? This tension-between empathy and accountability-defines the artistry of therapy.

The solution doesn't lie in choosing one over the other; rather, it lies in harmonizing attunement with accountability. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) offers an exemplary framework for balancing these elements. DBT underscores the importance of validating clients’ experiences while also holding them accountable for change. It’s where Carl Rogers’ compassion meets the rigor of therapeutic confrontation.

DBT's proven success with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) demonstrates its broader applicability. The same principles hold for other areas, including Autism, Social Phobia, ADHD, and PTSD. Empathy creates the foundation for rapport, while accountability propels the client toward growth.

Confrontation is often misunderstood as a harsh or antagonistic act. Popular culture has painted confrontations as tense, high-stakes interventions. But therapeutic confrontation, when grounded in compassion and honesty, can foster profound growth.

Early in my career, I struggled with my biases against confrontation. My personal history with avoidance reinforced my resistance to challenging clients directly. Over time, I realized that avoiding confrontation was more about my discomfort than theirs. Failing to address patterns directly meant colluding with the very dynamics clients needed to break free from.

Therapy asks us to sit with discomfort—for both our clients and ourselves. If you find yourself uneasy at the thought of confrontation, take a moment to reflect. What personal history might influence your hesitation? By exploring our biases and practicing immediacy, we model what it means to face the difficult truths of life with courage.

Facing undertreatment requires intentionality. Here are actionable strategies to ensure we hold ourselves accountable as therapists while offering the best care possible:

Seek Consultation

Consult with more experienced therapists or specialists when faced with challenging cases. Their insights can illuminate blind spots and provide fresh perspectives.

Invest in paid consultation sessions to access specialized advice. These structured opportunities are invaluable for deepening your understanding of specific issues.

Refer When Necessary

Sometimes, the best support we can offer is transitioning a client to a higher level of care. This decision, though difficult, centers the client’s well-being and ensures they receive the intensity of support required.

Feelings of annoyance or frustration that arise during therapy sessions should not be dismissed. Instead, they can serve as signposts pointing toward treatment-interfering behaviors or dynamics mirroring the client’s external relationships. Ask yourself, "Is this annoyance mine? Or is it reflective of something those around my client might also experience?"

Such reflections enrich therapy, turning discomfort into an invitation for curiosity and growth.

Therapy is a multifaceted dance that balances warmth, empathy, and genuine accountability. By addressing barriers with compassion and immediacy, we honor the therapeutic process while fostering meaningful change.

If you’re wrestling with difficult moments in therapy, remember this metaphor a former professor shared with me—just as breaking eggs and stirring them vigorously leads to a satisfying omelette, confronting discomfort leads to transformation. Prioritizing clients’ best interests sometimes requires navigating complex, challenging dynamics, but the rewards are well worth the effort.

Every step of this dance, no matter how small or uncomfortable, moves us closer to shared growth.

Exploring the critical role that ethics play in the field of mental health and the impact it has on both professionals and their clients. For the...

Cults have a strange allure. Like many others, I find myself riveted by shows and documentaries that explore their dynamics. There is disbelief,...

In the hushed confines of therapy rooms, where whispered truths echo and one's inner world unfolds, therapists often find themselves facing an...